The Goldilocks Sites page identified that there are many current public housing sites that could support Bluefield development. These sites come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Potential tenants of these sites also have unique needs and requirements of their home. As there are many sites, it is not feasible to design each site individually.

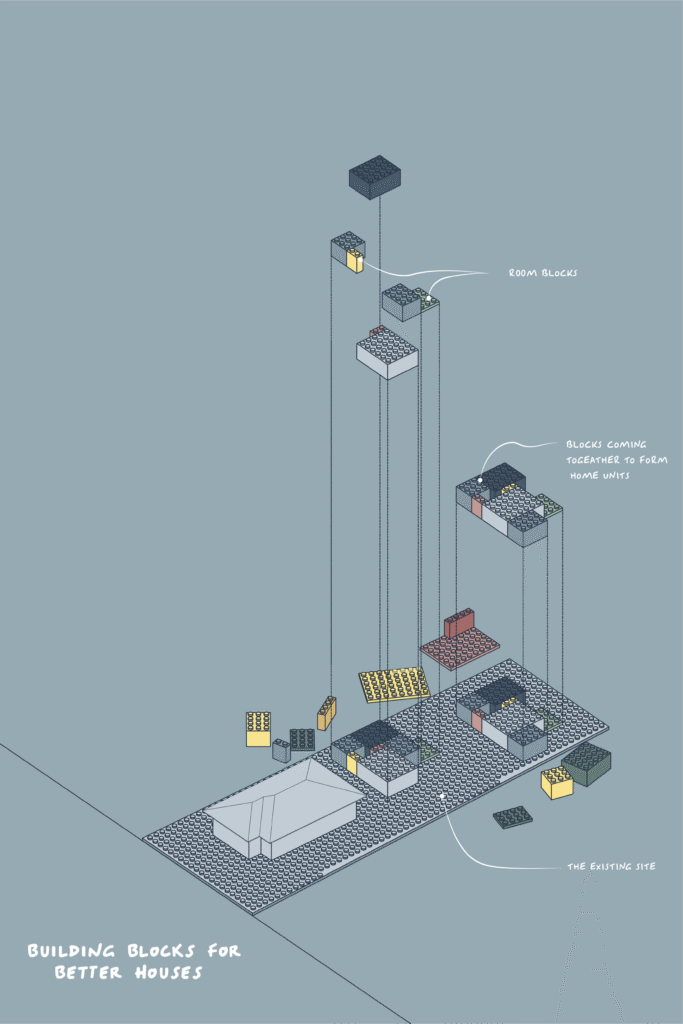

This page explains how the design process could be streamlined by breaking down specific spaces into a series of standardised blocks. These blocks can be combined and arranged in different ways to respond to specific sites or specific tenants’ needs. This approach allows flexible design responses, ensuring that no two sites would ever need to look the same. It also provides a scalable design response, ensuring that designs are developed efficiently, without the need to start from scratch each time.

Developing a brief

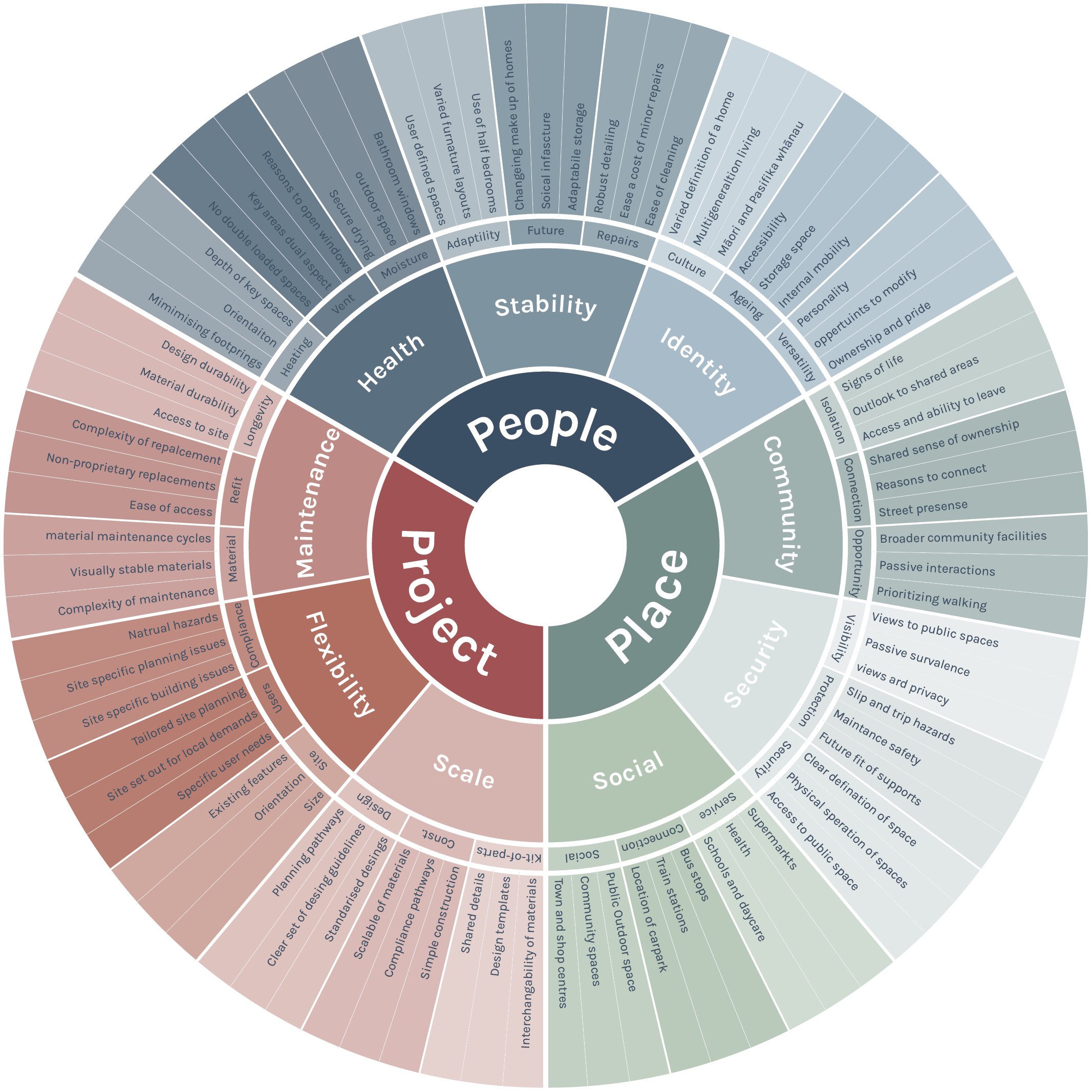

Before commencing design work, it is essential to develop a clear brief — a set of criteria against which potential design outcomes can be evaluated for overall success. A strong brief should highlight both opportunities and challenges, ensuring the design process is guided by well-defined objectives.

This brief was informed by a review of published studies: research into public housing tenants, with particular focus on their relationship to their homes, as well as architectural studies exploring infill and social housing.

The brief has been distilled into the diagram below. At the centre sit three core categories: People, Place, and Project. People relates to the lived experience of public housing residents; Place considers the types of environments Bluefield developments could create; and Project addresses the delivery and practical execution of development. A successful design must find balance across all three.

Each core category is broken down into several sub-categories, which are further expanded into prescriptive action points on the outer ring of the diagram. In total, there are 81 such action points. The more a design responds to the action points, the stronger and more effective it can be considered.

Building blocks

With such a large number possible sites and a high demand for public housing, there needs to be a degree of design standardisation so that new homes can be built efficiently. Classic design standardisation seeks to provide a blueprint for a whole house that can be used on multiple sites without much customisation. Although great in theory, this does not provide the flexibility needed to suit a wide range of sites and tenants.

The key is to standardise the design of rooms, instead of standardising the design of the whole house. Using this approach, each room can be considered a “building block”, to be pieced together with other blocks to create a home. These blocks can be configured in multiple different ways to suit the needs of different sites, without having to start from the beginning each time a new house is needed.

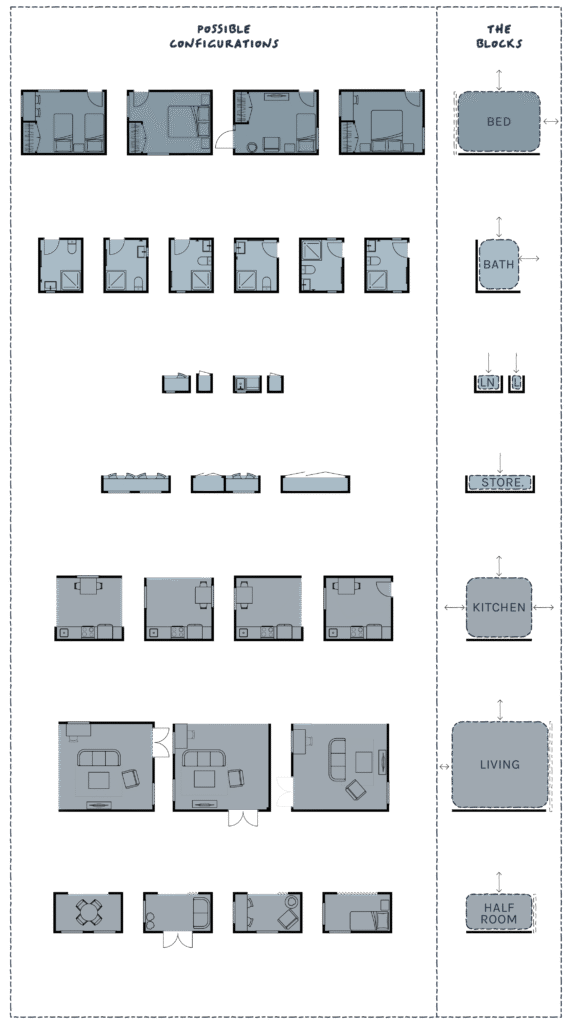

Each block needs to flexible, to suit different layouts and uses by different tenants. To show how this could work in practice, this research project has created a set of blocks that could be used to design public houses in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The set of blocks has one set of standardised dimensions for each room. Each block has been tested with multiple different layouts to ensure each space could support a wide range of uses. This flexibility is critical; by designing rooms that work with different arrangements, homes remain adaptable to the changing needs of households over time. These rooms and potential layouts can be seen in the diagram on the left.

As mentioned above, these blocks can be arranged in different ways, with more blocks added for the bigger homes needed for larger families, and fewer blocks for people living independently. Narrow infill sites, corner lots, or larger clusters can all be addressed with variations drawn from the same system. The consistency of the blocks supports efficient design and construction, but the arrangement creates variety – no two homes need look the same.

Arranging the blocks

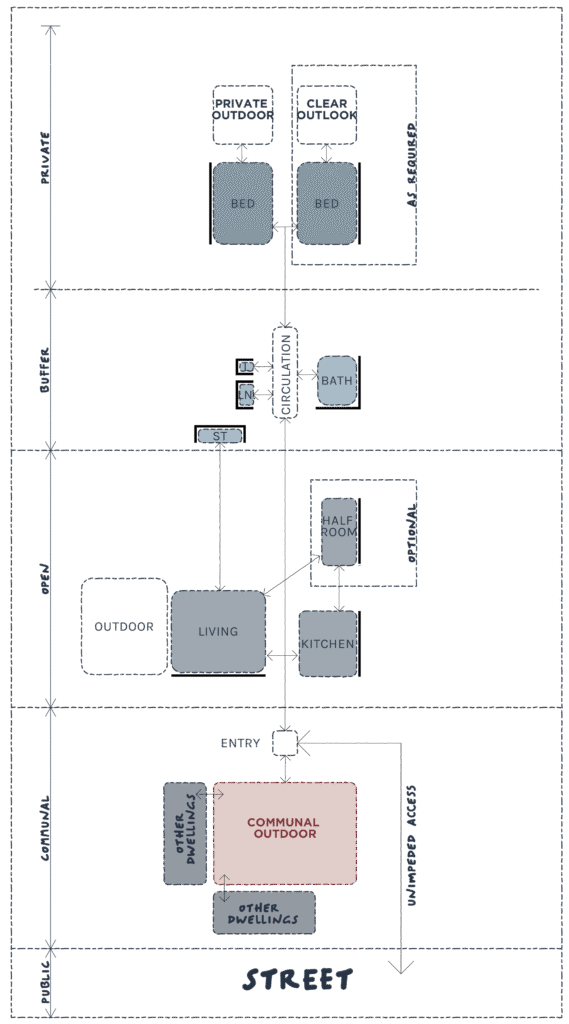

How blocks are ordered on a site shapes how a home is experienced – not just in terms of layout, but in how openness, security, and privacy are balanced. Spaces can be arranged in a way that meets the brief, and therefore the needs of public housing tenants.

To do so, primary living areas should be positioned to face communal spaces and orient towards the street. This creates natural opportunities for passive surveillance, where residents keep an eye on their surroundings, and also provides visible “signs of life” that help strengthen and social connection.

Beyond the living areas, a sequence of buffer spaces can be used to create transition between types of spaces. Elements such as storage, linen cupboards, laundries, bathrooms, and circulation corridors act as a shield between the public-facing zones of the house and the more private ones. This intermediate layer softens the shift from shared spaces into areas where privacy is most valued.

After the buffer zones, the private spaces should be positioned. Private spaces, such as bedrooms and personal outdoor areas, should not be directly exposed to communal zones or street activity. This creates feelings of both comfort and security.

A key benefit of this approach to arranging homes is that it reduces the need for hard boundaries, such as tall fences completely surrounding a property. Instead, the house itself provides much of the separation between public and private realms. Living rooms and kitchens signal activity to the outside world, buffer zones manage the transition, and bedrooms remain sheltered retreats. By letting the structure of the home carry much of the work of privacy, neighbourhoods can remain more open, encouraging natural interaction between residents and helping communities grow stronger through everyday connection.

Putting it all together

The strength of a modular system like “building blocks” is that it can adapt to sites of many shapes and sizes. A home is always formed from a larger cluster of blocks, and as more blocks are added, the home can expand to suit bigger households or more complex needs. On smaller sites, a compact arrangement of clusters creates efficient dwellings. In every case, the planning responds directly to the scale of the sites, producing housing that feels tailored rather than imposed.

This flexibility builds on the Goldilocks analysis, which identified sites across Aotearoa New Zealand that are “just right” for development. By starting with parcels that already have the right balance of size, slope, and location, the block system ensures that new housing can be introduced efficiently, without forcing awkward fits or overbuilding. The result is a framework that works as comfortably on a narrow infill lot as it does on a larger cluster site.

The adjoining image illustrates how this works in practice: as a site grows or shrinks, the layouts adjust and reconfigure themselves to suit its scale. This shows how the same set of blocks can generate very different outcomes, ensuring that housing responds sensitively to both the site and the community around it.

The communal areas

With multiple homes on one site, there will be shared spaces where residents can interact. These are the communal areas made up on spaces between the houses. Each site’s communal space will vary in size depending on the size of the lot and arrangement of buildings.

Instead of a backyard that is barely used or hard to maintain, there is an opportunity to use these spaces to foster a sense of connection. Given outdoor spaces are easier to change than buildings themselves, there is also an opportunity to involve tenants in how they are designed and used.

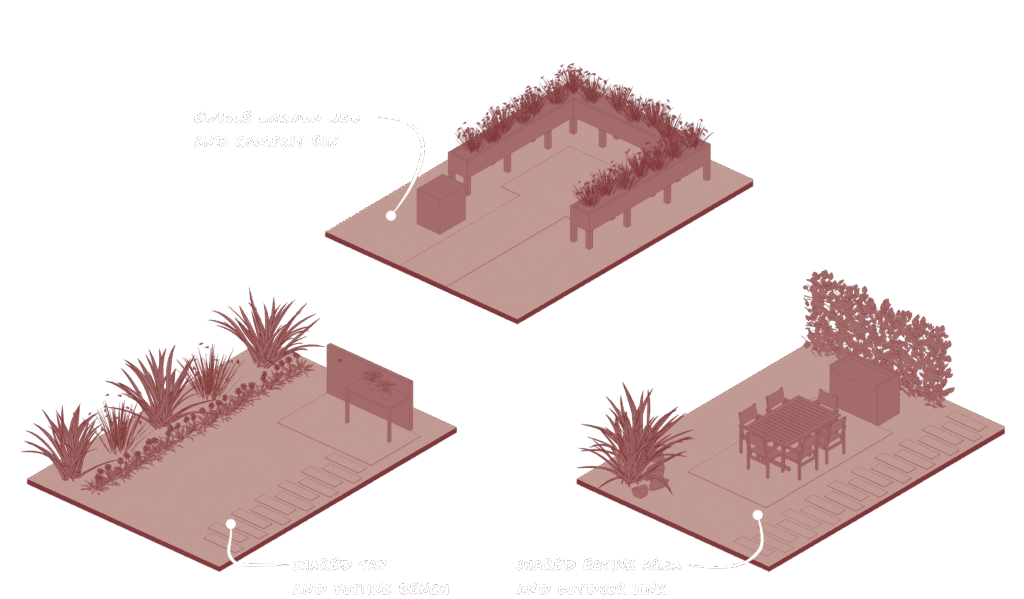

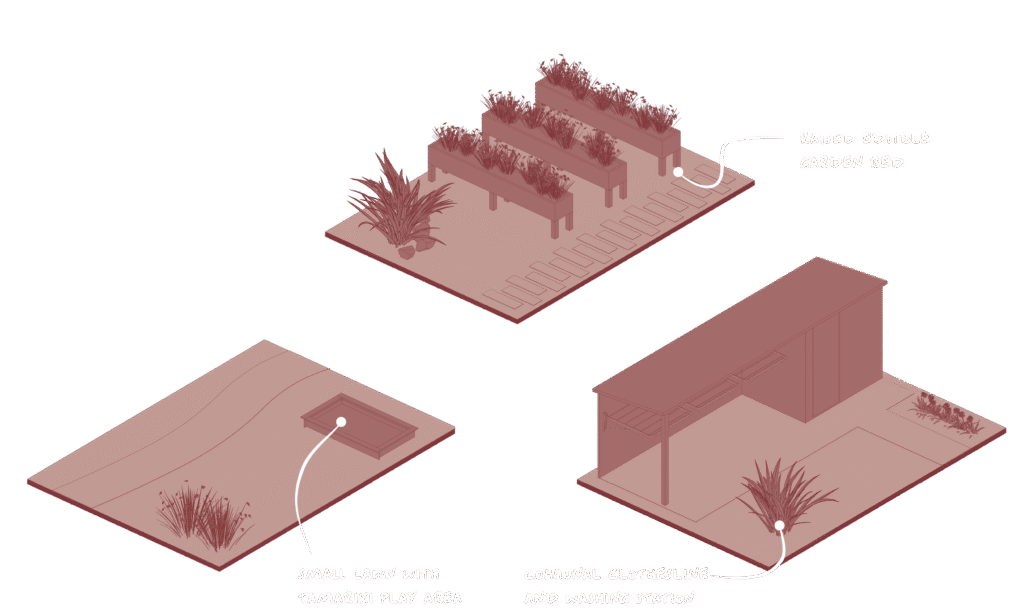

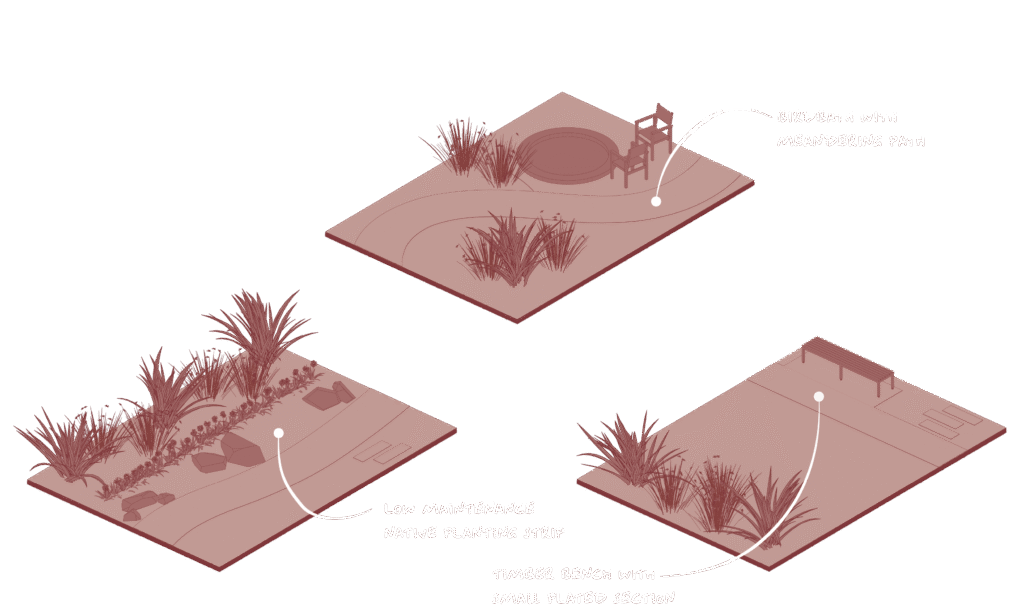

As part of this project, a set of kits has been designed to create communal spaces in the homes built using the methodology above. Given the ease of changing these sorts of spaces, the kits do not have to be followed exactly. They could be adapted to fit the needs of tenants.

Some of the kits are more active and social, such as traditional communal areas for cooking, eating, and gathering. Others are quieter and more passive, such as a native garden or planting.

To create a sense of ownership and connection, tenants could select and adapt the kits that best match their needs, values, and ways of living. In this way, communal areas become not just shared amenities, but spaces of belonging and community connection.

The examples in the dropdown below show four communal kits that illustrate how this works in practice.

The Shared Gathering Kit creates an outdoor “third room” where neighbouring households can meet in a relaxed, neutral setting. By introducing elements such as pavers, gravel, or timber decking, the space is subtly defined without feeling overly formal, encouraging casual interaction. Practical features like a shared tap with potting bench, edible garden beds with composting, or a communal BBQ slab and sink allow the area to support everyday use as well as special occasions.

The Whānau Everyday Kit is designed to support households with young children, where daily routines and supervision are central to family life. It focuses on safe, durable spaces that allow kids to play and explore while staying within clear sightlines of the kitchen and living areas. By combining practical features like communal clotheslines and washing stations with playful touches such as edible garden beds and small lawns, this kit blends the functional with the fun.

The Quiet Retreat Kit is designed as a calm outdoor space, offering residents a buffer from the busyness of daily life. Prioritising privacy, shade, and enclosure, it softens the edges of housing with planting, natural textures, and places to pause. Low-maintenance native strips, bird baths, and timber benches beneath dappled light bring calm and connection to the natural environment. These spaces nurture wellbeing, creating small sanctuaries for reflection and rest

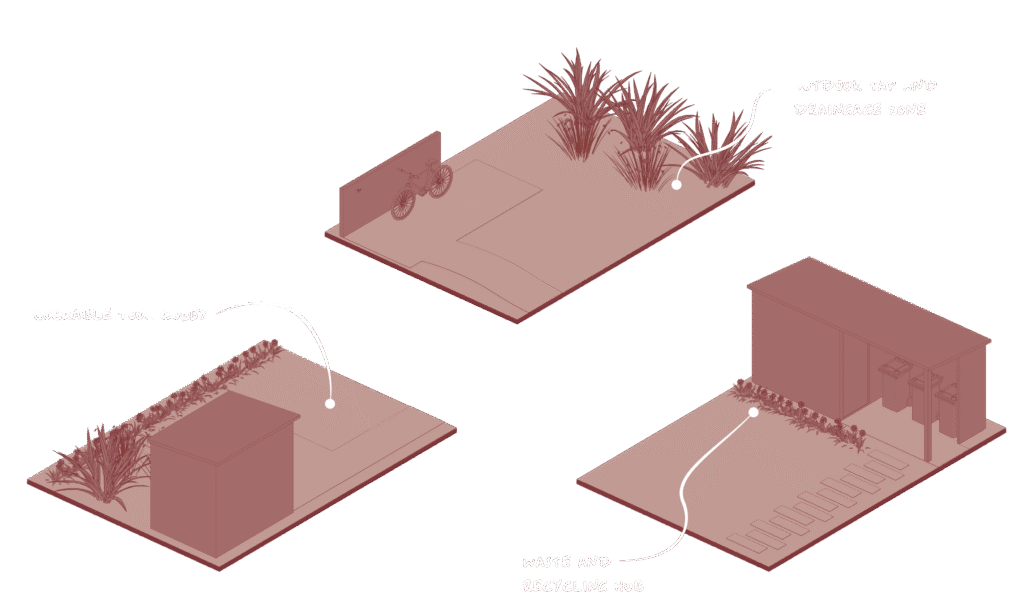

The Practical Care Kit brings order and functionality to outdoor areas where space is tight and daily routines are essential. It focuses on neat, practical solutions that support chores such as cleaning, storing, and sorting, while still leaving room for greenery. An outdoor tap and drainage area, a secure cupboard for tools, and a clear hub for waste and recycling make it easy to look after both home and environment. This kit turns necessary routines into simple, manageable activities.

Adapting to the site

The adjacent image shows the strength of “building blocks” as a system. As the size and shape of the site changes, the building blocks system adapts to